427 Life in Space

These are the most sensible words about the position of humans in the universe I

have read yet. I reprint the whole

article from The Telegraph, London, via the SMH; here is the juicy bit …

“... our solar system is

barely middle aged and if we humans avoid self-destruction, the

"post-human" era beckons. Prolonged interstellar travel wouldn't be a

challenge to near-immortal "post-humans". Alternatively, small

spacecraft could carry genetic material, or "blueprints", via laser

transmission ("space travel" at the speed of light). And these could

trigger the assembly of living organisms in propitious (favourable) locations. Life seeded

from Earth could spread through the entire galaxy, evolving into a teeming

complexity far beyond what we can conceive. If so, our tiny planet - this pale

blue dot floating in space - could be the most important place in the entire

cosmos.”

This concept is not new to me at all. I have read about it many, many years ago in Frank Tipler's book The Physics of Immortality ... I have an essay about it MATRIX, in my book with not title but three definitions for the term en.light.en.ment

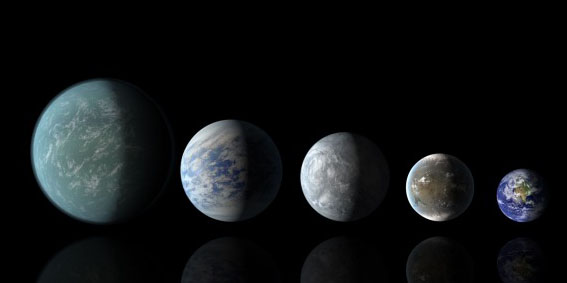

NASA's Kepler Space Telescope is

searching for rocky planets that can hold liquid water.

Photo: NASA

The starry sky is now far more

fascinating to us than it ever was to our forebears. Stars may seem just points

of light, but we've learnt recently that most are orbited by retinues of

planets, just as our sun is. Our galaxy probably harbours many billions of

planets. The most fascinating question of all is how many might harbour life –

even intelligent life? Could Kepler 438b be part of the answer?

Kepler 438b is a very Earth-like

planet whose discovery was announced this week. There's special interest in

"twins" of our Earth – planets the same size as ours, orbiting other

Sun-like stars. Kepler 438b is one of those. It's 475 light years away, and

it's on an orbit in the "Goldilocks zone" – not so close to its star

that water boils away, nor so far that it's perpetually icy. It was discovered

by the small telescope on board Nasa's Kepler spacecraft, which monitored the

brightness of 150,000 stars for more than three years. Some stars underwent

slight regular dimmings, caused by orbiting planets that transit in front of

them, blocking out a bit of their light.

The Kepler data has already revealed

many surprises. Our solar system may be far from typical. In some systems,

planets as big as Jupiter are circling so close to their star that their

"year" lasts only a few days. Some planets orbit binary stars – there

would be two "suns" in their sky. But we'd really like to see these

planets directly – not just their "silhouettes" as they pass in front

of their parent star. And that's hard. To realise just how hard, suppose an

alien astronomer with a powerful telescope was viewing the Earth from 30 light

years away – the distance of a nearby star. It would seem, in Carl Sagan's

phrase, a "pale blue dot", very close to a star (our sun) that far

outshines it: a firefly next to a searchlight.

But if the aliens could detect

Earth, they could learn quite a lot about it. The shade of blue would be

slightly different, depending on whether the Pacific Ocean or the Eurasian land

mass was facing them. They could infer the length of our day, the seasons, that

there are continents and oceans, and the climate. By analysing the faint light,

they could infer that the Earth had a biosphere.

We don't yet have telescopes

powerful enough to make such observations of planets beyond our solar system.

But before 2030, the unimaginatively named ELT ("Extremely Large

Telescope") planned by European astronomers will offer the combination of

light-gathering power and sharpness of imaging to draw such inferences about

those planets orbiting nearby, Sun-like stars. The ELT will have a mirror 39

metres across (actually a mosaic of 800 sheets of glass). A mountaintop in

Chile has been levelled to provide the optimum site; construction will soon

begin.

But should we expect life on these

distant worlds? It's the uncertain biology that's the main stumbling block. We

know how simple life evolved into our present biosphere. But we don't know how

the first life was generated from a "soup" of chemicals. It might

have involved a fluke so rare that it happened only once in the entire galaxy –

like shuffling a whole pack of cards into a perfect order. On the other hand,

this crucial transition might have been almost inevitable given the

"right" environment.

The stakes are so high that it's

surely worth searching for evidence of advanced alien life, though we may not

be able to recognise it. For some alien "brains" may package reality

in a fashion that we can't conceive of, and have a quite different perception

of reality. Others could be uncommunicative: living contemplative lives,

perhaps deep under some planetary ocean. The most durable form of

"life" may be machines whose creators had long ago been usurped or

become extinct. There may be a lot more out there than we could ever detect.

Absence of evidence wouldn't be evidence of absence.

Perhaps we'll one day "plug

in" to a galactic community. On the other hand, Earth's intricate

biosphere may be unique. But that would not render life a cosmic sideshow.

Interstellar travel in our lifetimes isn't realistic (the magic tricks used in

the movie Interstellar are, sadly, science fiction). But humans aren't the

culmination of evolution. Our solar system is barely middle aged and if we

humans avoid self-destruction, the "post-human" era beckons.

Prolonged interstellar travel wouldn't be a challenge to near-immortal

"post-humans". Alternatively, small spacecraft could carry genetic

material, or "blueprints", via laser transmission ("space

travel" at the speed of light). And these could trigger the assembly of

living organisms in propitious locations.

Life seeded from Earth could spread

through the entire galaxy, evolving into a teeming complexity far beyond what

we can conceive. If so, our tiny planet – this pale blue dot floating in space

– could be the most important place in the entire cosmos.

Lord Martin Rees is

the Astronomer Royal

The Telegraph,

London