Leo Tolstoy, truth and non-violence

Leo

Tolstoy says in his book The Kingdom of God is within You: “The sole meaning of life is to serve

humanity by contributing to the establishment of the Kingdom of God within,

which can only be done by the recognition of the truth (and should be done) by

every human” and “there is one thing, and only one thing, in which it is

granted to you to be free in life, all else being beyond your power: that is to

recognize and profess the truth.”

I quote him again in the footnote to my essay FREE WILL: “The champions of the metaphysics

of hypocrisy say: ‘Man cannot change his life, because he is not free. He is

not free, because all his actions are conditioned by previously existing

causes; so whatever he does, these acts mean that man cannot be free and change

his life.'

"And they would be perfectly right if man were a creature without

conscience and incapable of moving toward the truth; that is to say, if after

recognizing a new truth, man remained always at the same stage of moral

development. But man is a creature of conscience. Thus man is capable of

attaining a higher and higher degree of truth. And therefore, even if man is

not free as regards performing certain acts because of pre-existing causes, the

very causes of his acts, consisting as they do of the recognition of truth, are

within his own control’.”

“Whatever the conscious

man does, he acts just as he does, and not otherwise, only because he

recognizes that to act as he is acting is in accordance with the truth, or

because he has recognized it at some previous time, and is now only through inertia,

through habit, acting in accordance with his previous recognition of truth.”

I mentioned Tolstoy before, in my blog 479 about Self-knowledge; see also my blogs 482, 488 about truth.

With content from Wikipedia

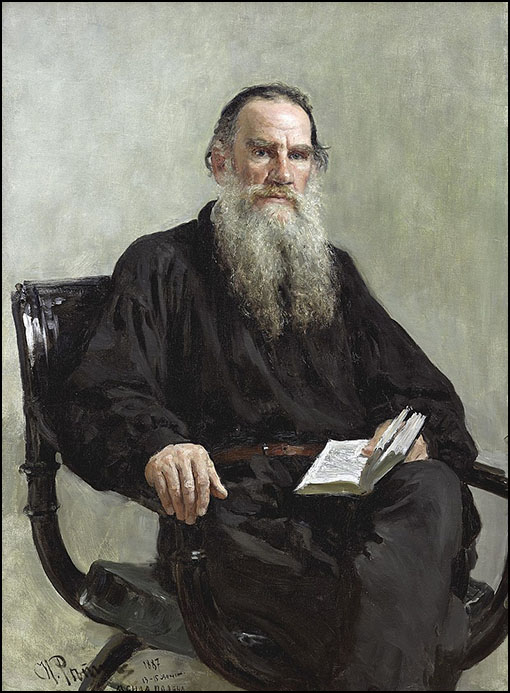

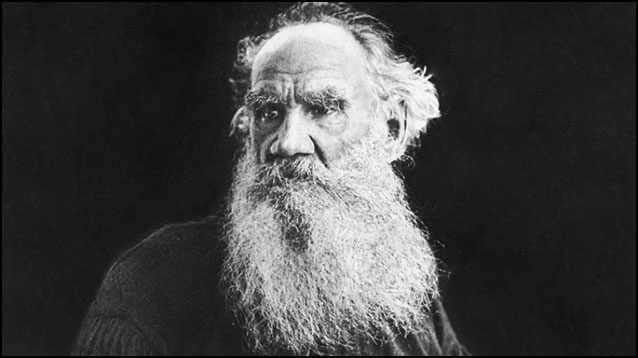

Leo Tolstoy (1828 - 1910), born to an aristocratic Russian family, was a champion of the truth and an advocate of peace and

non-violence, even in the face of evil.

Tolstoy is best known for the novels War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1877). He wrote them with his wife Sonya as his secretary, editor, and financial manager. Sonya was copying and handwriting his epic works time after time (below a page from his ninth draft; incidentally, she also had 13 children with him). Tolstoy would continue editing War and Peace and had to have clean final drafts to be delivered to the publisher.

I can't help myself, but I have to add a comment here: Can anyone imagine the magnitude of this task? They wrote the books by hand (in print 1440 pages, Book Depository), and his wife copied and edited this book - War and Peace - nine times! Furthermore, he wrote his second great opus a mere eight years after the first (and who knows how many pieces of writing in-between). Now, I write my book en.light.en.ment - of course - on the computer; I published it first in 2012. The current edition is no. 48. But I have made 328 revisions to date. I am in awe of this man and his wife (and for that matter, any writer of the pre-typewriter/pre-computer eras).

In 1844, he began studying law and oriental languages, his teachers

described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn." Tolstoy left

the university in the middle of his studies and in 1851, after running up heavy

gambling debts, he and his older brother joined the army.

It was about this time that he started writing. Tolstoy was promoted to lieutenant for "outstanding bravery and courage". His conversion from a dissolute and privileged society author to the non-violent and spiritual anarchist of his latter days was brought about by his experience in the army. Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that would mark him for the rest of his life. Writing in a letter: "The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere."

Tolstoy's

concept of non-violence was instilled in Mahatma Gandhi through his A Letter

to a Hindu when young Gandhi corresponded with him seeking his advice. His

European trip shaped both his political and literary development and Tolstoy

wrote his educational notebooks. Fired up by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to

Russia and founded 13 schools for the children of Russia's peasants, who had

just been emancipated from serfdom in 1861.

Tolstoy's educational experiments

were short-lived, however, as a direct forerunner to A. S. Neill's Summerhill

School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed the first

example of a coherent theory of democratic education. I am interested in these

developments in view of my UNITY project.

After reading Schopenhauer's The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy

gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in that work as the

proper spiritual path for the upper classes: "Do you know what this summer

has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of

spiritual delights which I've never experienced before. ... no student has ever

studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer."

In Chapter VI of A Confession, Tolstoy quoted the final

paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. It explained how the nothingness that results

from complete denial of self is only a relative nothingness, and is not to be

feared. The novelist was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and

Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading

passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical

chapters, the Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will:

But this

very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for eternal salvation

is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (Matthew 19:24): "It is

easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to

enter into the kingdom of God." Therefore those who were greatly in earnest

about their eternal salvation, chose voluntary poverty when fate had denied

this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus Buddha Sakyamuni was born a

prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant's staff; and Francis of Assisi,

the founder of the mendicant orders who, as a youngster at a ball, where the

daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: "Now

Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?" and who

replied: "I have made a far more beautiful choice!" "Whom?"

"La povertà (poverty)": whereupon

he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a

mendicant.

In 1884, Tolstoy wrote a book called What I Believe, in which he openly

confessed his Christian beliefs. He affirmed his belief in Jesus Christ's

teachings and was particularly influenced by the Sermon on the Mount, and the

injunction to turn the other cheek, which he understood as a "commandment

of non-resistance to evil by force" and a doctrine of pacifism and nonviolence.

In his work The Kingdom of God Is Within You, he explains that he considered a mistake the Church's doctrine because they had made a "perversion"

of Christ's teachings.

Tolstoy also received letters from

American Quakers who introduced him to the non-violence writings of Quaker

Christians such as George Fox, William Penn and Jonathan Dymond. Tolstoy

believed being a Christian required him to be a pacifist; the consequences of

being a pacifist, and the apparently inevitable waging of war by government,

are the reason why he is considered a philosophical anarchist.

Later, various versions of "Tolstoy's Bible" would be

published, indicating the passages Tolstoy most relied on, specifically, the

reported words of Jesus himself.

Tolstoy believed that a true

Christian could find lasting happiness by striving for inner self-perfection

through following the Great Commandment of loving one's neighbor and God rather

than looking outward to the Church or state for guidance. His belief in

nonresistance when faced by conflict is another distinct attribute of his

philosophy based on Christ's teachings.

By directly influencing Mahatma

Gandhi with this idea through his work The

Kingdom of God Is Within You (full text of English translation available on

Wikisource), Tolstoy's profound influence on the nonviolent resistance movement

reverberates to this day. He believed that the aristocracy were a burden on the

poor, and that the only solution to how we live together is through anarchism.

Leo Tolstoy vs. the World

from Russia Beyond

Leo Tolstoy was never easy-going.

Having built his own philosophical and religious system, Tolstoy fought anyone

opposing it, including the state and the Russian Orthodox Church. No one could

stop the redoubtable author.

In 1884 he ironically asked his aunt

to consider him a Muslim. He didn’t really convert to Islam; it was a way to

emphasize Tolstoy’s loneliness and his endless conflicts in Russian society.

“Liberals think of me as an insane man, radicals – a babbler mystique, the

government considers me a dangerous revolutionary and the Church thinks I’m the

Devil himself,” Tolstoy wrote.

Back in the 1880s, Tolstoy who had

already written his masterpieces War and Peace and Anna

Karenina, now concentrated on philosophical writings and was extremely

popular in Russia with hundreds of people adoring him (starting from the

emperor Alexander III who called him “my Tolstoy”).

Nevertheless, he sparked serious

disputes in society as his views were radical and contradicted the official

line of both government and church. Here are three holy wars that Leo Tolstoy,

Russian “king of controversy”, took part in.

Tolstoy vs. the State

Leo Tolstoy didn’t love the government.

Not only the Russian one but also the idea in general. As he wrote to

the North American newspaper in 1904, during the

Russo-Japanese war, “I am not for Russia nor for Japan, but for the working

classes of both countries, which have been forced to war.”

In other words, the author was a

self-consistent anarchist. As philologist Andrei Zorin pointed out, since

Tolstoy’s childhood the whole idea of suppressing the individual (and power,

even balanced and limited, does that) was violent and unacceptable for him.

His humanism opposed any

powers-that-be, thus making him a dangerous liberal for those in charge.

Tolstoy believed that climbing to the top of the society required cunning and

dirty tricks, so it’s the worst people who rule the world.

At the same time, Tolstoy was never

a revolutionary, as he did not believe in violent means. Although Vladimir

Lenin, the future leader of the USSR, called Tolstoy “the mirror of the Russian

revolution” for his description of deep contradictions in Russian society, he

criticized the author for “incoherent” views and insufficient criticism of the

government. Tolstoy didn’t care, preferring the spiritual to political life.

But in this area he had even more serious conflicts.

Tolstoy vs. the Orthodox Church

Leo Tolstoy didn’t love the

government. Not only the Russian one but also the idea in general. As he wrote to

the North American newspaper in 1904, during the Russo-Japanese

war, “I am not for Russia nor for Japan, but for the working classes of both

countries, which have been forced to war.”

In other words, the author was a

self-consistent anarchist. As philologist Andrei Zorin pointed out, since

Tolstoy’s childhood the whole idea of suppressing the individual (and power,

even balanced and limited, does that) was violent and unacceptable for him.

His humanism opposed any

powers-that-be, thus making him a dangerous liberal for those in charge.

Tolstoy believed that climbing to the top of the society required cunning and

dirty tricks, so it’s the worst people who rule the world.

At the same time, Tolstoy was never

a revolutionary, as he did not believe in violent means. Although Vladimir

Lenin, the future leader of the USSR, called Tolstoy “the mirror of the Russian

revolution” for his description of deep contradictions in Russian society, he

criticized the author for “incoherent” views and insufficient criticism of the

government. Tolstoy didn’t care, preferring the spiritual to political life.

But in this area he had even more serious conflicts.

A believer all his life, from a

certain point Tolstoy separated ways with the official Orthodoxy. Back in 1855

(in his twenties), he mentioned in his diary that his aim was to create a new

religion – Christianity “purified” of mysticism. He and his supporters,

believing in Christ and considering themselves Christians, called for focusing

on living this life wisely and righteously, not waiting for the afterlife.

Tolstoy advocated strict moral norms

implied by the Church but denied miracles. For example, for him Christ hadn’t

resurrected after being crucified in Jerusalem: he was only a righteous man,

not a Son of God. Such an approach, “Christianity with no wonders,” triggered

outrage among church officials.

As it wasn’t enough, Tolstoy loved

to criticize them harshly, calling Russian priests “self-confident but lost and

poorly educated, dressing in silk and velvet.” To him, the Church corrupt with

power and money, couldn’t be a moral authority and was only enslaving the

peasants.

The Church leaders spared no

criticism towards Tolstoy. Presbyter John of Kronstadt, one of the most popular

Christian preachers of those days (later canonized), described Tolstoy like

this: “He perverted all the sense of Christianity… he laughs at Church with

Satan’s laughter.” He even prayed for Tolstoy’s death in 1908.

These anarcho-pacifist views along

with his huge popularity and criticism of the priests led to Tolstoy's

excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901. Tolstoy recognized

the act, agreeing that he disbelieved church dogmas and it would be

hypocritical to be part of the Church. His excommunication remains valid in the

Orthodox Church and no cross marks his grave.

Tolstoy vs. Shakespeare

Unlike church and state, William

Shakespeare, who also suffered from Tolstoy’s severe criticism couldn’t answer

him for he had been dead since 1616. This, however, didn’t stop one of the

greatest Russian writers from destroying (or, rather, trying to destroy) one of

the most famous British.

“There is no real human talk in his

plays,” Tolstoy wrote in a big essay dedicated to Shakespeare’s heritage. He

also expressed that he felt “irresistible repulsion and tedium” while reading

the plays, no matter what language he tried - Russian, English or even German.

It’s unlikely that Tolstoy thought

that his criticism would undermine Shakespeare’s influence but he couldn’t help

but write all in which he believed. Even while attacking plays of his fellow

writer Anton Chekhov, count Tolstoy used Shakespeare as an example: “Anton

Pavlovich, Shakespeare was a bad writer, and I consider your plays even worse.”

History proved him wrong: both Chekhov and Shakespeare are still being staged

throughout the world.

Tolstoy rejected the Nobel Prize

When the first Nobel Prize winner,

the French poet Rene Sully-Prudhomme, was announced in 1901, many of Tolstoy’s

admirers were disappointed. This was especially true in the Swedish literature

circle, where Tolstoy was considered as the ideal candidate for the award.

Several years passed, but Tolstoy

did not appear on the list of nominees. In 1906 the Academy of Sciences in St.

Petersburg submitted an application in support of the author’s nomination. When

Leo Tolstoy learned of the rumour that he should be the Nobel Laureate, he

wrote a letter to Arvid Jarnefelt, his Finnish translator, asking him to remove

his name from the list of nominees. He wrote that it would be extremely

uncomfortable to have to reject the prize if he won. Jarnefelt sent a

translation of the letter to the committee, and in the end, the Nobel Prize

went to the Italian poet Carducci Geosue, who was only well-known amongst

literary specialists.

Leo Tolstoy was the only nominee to

have asked discreetly for the removal of his name, and also to refuse the prize

money of $100,000. Some years later, when the public was again outraged that

Tolstoy was not nominated, he wrote:

“First, it has saved me the

predicament of managing so much money, because such money, in my opinion, only

brings evil. Secondly, I felt very honoured to receive such sympathy from

people I have not even met. ”